Holidays

People often say: “The Jewish holidays are late this year” or “The Jewish holidays are early this year.” In fact, the holidays never are early or late; they are always on time, according to the Jewish calendar. Unlike the Gregorian (civil) calendar, which is based on the sun (solar), the Jewish calendar is based primarily on the moon (lunar), with periodic adjustments made to account for the differences between the solar and lunar cycles.

Therefore, the Jewish calendar might be described as both solar and lunar. The moon takes an average of 29.5 days to complete its cycle; 12 lunar months equal 354 days. A solar year is 365 1/4 days. There is a difference of 11 days per year. To ensure that the Jewish holidays always fall in the proper season, an extra month is added to the Hebrew calendar seven times out of every 19 years. If this were not done, the fall harvest festival of Sukkot, for instance, would sometimes be celebrated in the summer, or the spring holiday of Passover would sometimes occur in the winter.

Holidays

You can celebrate the Jewish holidays at our Temple Emanu-EL, including Passover, Purim, Sukkot, Hanukkah, and Shavuot. These holidays hold deep historical and religious significance, serving as occasions for prayer, reflection, and community gatherings, and reinforcing the cultural and spiritual identity of our Jewish community.

SUKKOT

Sukkot, a Hebrew word meaning “booths” or “huts,” refers to the Jewish festival of giving thanks for the fall harvest, as well as the commemoration of the forty years of Jewish wandering in the desert after Sinai. Sukkot is celebrated five days after Yom Kippur on the 15th of Tishrei and is marked by several distinct traditions.

One tradition, which takes the commandment to “dwell in booths” literally, is to build a sukkah, a booth or hut. A sukkah is often erected by Jews during this festival, and it is common practice for some to eat and even live in these temporary dwellings during Sukkot.

SIMCHAT TORAH

Simchat Torah, Hebrew for “rejoicing in the Law”, celebrates the completion of the annual reading of the Torah. Simchat Torah is a joyous festival, in which we affirm our view of the Torah as a tree of life and demonstrate a living example of never-ending, lifelong study. Torah scrolls are taken from the ark and carried or danced around the synagogue seven times. During the Torah service, the concluding section of Deuteronomy is read, and immediately following, the opening section of Genesis, or B’reishit as it is called in Hebrew, is read.

HANUKKAH

Hanukkah, meaning “dedication” in Hebrew, refers to the joyous eight-day celebration during which Jews commemorate the victory of the Macabees over the armies of Syria in 165 B.C.E. and the subsequent liberation and “re-dedication” of the Temple in Jerusalem.

The modern home celebration of Hanukkah centers around the lighting of the hanukkiah, a special menorah for Hanukkah; unique foods, latkes and sufganiyot (jelly doughnuts); and special songs and games.

HANUKKAH AT HOME

A “wonder-full, worship-full” experience

Most of the popular rituals of Hanukkah are practiced at home. While the lighting of the menorah takes center stage, there are many meaningful ways to light up your family’s holiday celebration.

FOOD: The tradition of eating food cooked in oil reminds us of the legend of the long-lasting cruse of oil found during the Temple clean-up. Find recipes in books and magazines and do a latke or sufganiot tasting!

GIFTS: Choose one night of Hanukkah to pick an organization everyone in the family agrees on, and give a donation instead of giving gifts to each other. Or shop together for gifts that can be donated – food to a food bank or articles of clothing to an organization that helps those in need. Doing acts of Tikkun Olam together as a family can make your Hanukkah more meaningful.

DREIDEL: While the dreidel game might have originated as a German gambling game, it holds the central meaning of Hanukkah within the driedel’s four walls – Ness, Gadol, Haya, Sham – A Great Miracle Happened There!

MUSIC: Find Hanukkah songs on line, on iTunes, in stores. The joy of music enlivens our worship services at Temple Emanu-El. Let it do the same for your family at home.

Purim

We often think of Purim with its costumes and noisemakers as a children’s holiday. But its themes and ideas are of great importance to Jewish life. In fact, our tradition tells us that we are to drop whatever we are doing, no matter its importance, to go and listen to the story of Purim.

This story in the Book of Esther takes place in the land of Persia (today’s Iran) at the time when Ahashverosh (aka Ahasuerus) was king. King Ahashverosh held a banquet in his capital city of Shushan and ordered his queen,Vashti, to come and dance before his guests. She refused to appear and lost her royal position.

Based on advice from his counselors, Ahashverosh held a pageant to choose a new queen. Mordechai, a Jewish man living in Shushan, encouraged his cousin, Esther, to enter the competition. Esther won but, following the advice of her cousin, did not reveal her Jewish origin.

Mordechai often sat near the gate of the king’s palace. One day he overheard two men, Bigthan and Teresh, plotting to kill the king. Mordechai reported what he had heard to Esther. She then reported the information to the king. The matter was investigated and found to be true. Bigthan and Teresh came to an unfortunate end. Mordechai’s deed was recorded, but his actual reward came later.

Meanwhile, the king’s evil adviser, Haman, paraded through the streets, demanding that all bow to him. Mordechai refused, since Jews are not supposed to bow to anyone but God. Upon finding out that Mordechai is Jewish, Haman decided to kill all the Jews in the Persian empire. He plotted to kill them and cast purim (“lots,” plural of pur), a kind of lottery, to determine the day on which he would carry out his evil deed: the 13th of Adar. Haman also convinced King Ahashverosh to go along with his plan, although in the Megillah, Haman never identified the Jews as the people he wished to destroy.

He convinces the king to decree that all of the Jews in the land should be killed on the 13th of the month of Adar. Mordechai alerted Esther to Haman’s evil plot, and Esther revealed her Jewishness to the King and convinced him to save the Jews, foiling Haman’s plot. Haman was hanged, Mordechai received his estates and position of royal vizir, and the Jews of Persia celebrated their narrow escape on the 14th of Adar, the day after they were supposed to be annihilated.

Thus, the fate that Haman had planned for the Jews became his own. The holiday of Purim celebrates the bravery of Esther and Mordechai and the deliverance of the Jewish people from the cruelty of oppression.

Megillah means scroll, most often referring to Megillat Esther, literally “The Scroll of Esther,” also known as the “Book of Esther.”

Megillah means scroll, most often referring to Megillat Esther, literally “The Scroll of Esther,” also known as the “Book of Esther.”

According to the Talmud, “The study of Torah is interrupted for the reading of the Megillah.” And Maimonides (a 12th century sage and rabbi) teaches, “The reading of the Megillah certainly supersedes all other mitzvot.” (Maimonides,Yad, Megillah 1:1)

Traditionally, congregations gather together to read the Megillah at both the evening and morning services on Purim. When the name of Haman is read, congregants use noisemakers to drown out the sound of his name.

What does Purim celebrate?

Purim celebrates the Jews’ escape from extinction in Persia. In fact, their complete victory in the story is such an inversion of what might have happened that the holiday is celebrated with general silliness and merry-making.

What are some of the customs of Purim?

In the Book of Esther, we read that Purim is a time for “feasting and merrymaking” as well as for “sending gifts to one another and presents to the poor” (Esther 9:22). In addition to reading the Megillah, celebrants dress up in costumes; have festive parties; perform silly theatrical adaptations of the story of the Megillah called “Purim shpiels”; send baskets of food to friends, called mishloach manot; and give gifts to the poor, called matanot l’evyonim.

What are mishloach manot?

Mishloach manot are gifts of food that friends (and prospective new friends!) give to one another on Purim. Most include the traditional Purim food of hamantashen, but many include a wide variety of foods and treats. They’re also commonly referred to by their Yiddish name, shalachmanos.

What are hamantashen?

Hamantashen are three-cornered cookies made from dough with a filling in the center. The most popular fillings are apricot, cherry, poppy (also called mun), prune and chocolate.

What are Matanot l’evyonim?

Matanot l’evyonim are gifts to the poor so that they, too, can celebrate Purim with a special meal.

What is a Purim-shpiel?

A Purim-shpiel (pronounced SHPEEL, rhymes with “reel”) is a humorous skit presented on Purim. Most of them parody the story of the Book of Esther, but it is also common for congregations to take the opportunity to poke some gentle fun at themselves and their idiosyncrasies.

Shavuot

Shavuot is a Hebrew word meaning ‘weeks’ and refers to the Jewish festival marking the giving of the Torah at Mount Sinai. Shavuot, like so many other Jewish holidays began as an ancient agricultural festival, marking the end of the spring barley harvest and the beginning of the summer wheat harvest. Shavuot was distinguished in ancient times by bringing crop offerings to the Temple in Jerusalem.

The Torah tells us it took precisely forty-nine days for our ancestors to travel from Egypt to the foot of Mount Sinai (the same number of days as the Counting of the Omer) where they were to receive the Torah. Thus, Leviticus 23:21 commands: ‘And you shall proclaim that day (the fiftieth day) to be a holy convocation…’ The name Shavuot, ‘Weeks,’ then symbolizes the completion of a seven-week journey.

Special customs on Shavuot are the reading of the Book of Ruth, which reminds us that we too can find a continual source of blessing in our tradition. Another tradition includes staying up all night to study Torah and Mishnah, a custom called Tikkun Leil Shavuot, which symbolizes our commitment to the Torah, and that we are always ready and awake to receive the Torah. Traditionally, dairy dishes are served on this holiday to symbolize the sweetness of the Torah, as well as the ‘land of milk and honey’.

Shavuot is celebrated seven weeks after Passover (when the barley harvest begins). These seven weeks are called the Omer and are counted ceremonially. This counting, called s’firat ha-omer, begins on the second day of Passover.The source for this practice is found in the book of Deuteronomy, “You shall count off seven weeks…then you shall observe the Feast of Weeks to Adonai your God” (Deuteronomy 16:9-10). The counting of the Omer takes place daily after the evening service.

Once the Temple in Jerusalem was destroyed and the mitzvah of bringing the first fruits of the harvest was lost, the Rabbis were concerned that the observance of Shavuot might disappear. It was during this time period (2nd century C.E.) when the Rabbis determined that the revelation of Torah at Sinai coincided with Shavuot.

Passover

Passover is the quintessential Jewish holiday. We gather in our homes to celebrate with family and friends to replay the narrative of our people each in our unique way with festivity, feasting, and fun.

The story of Passover originates in the Bible as the story of the Exodus from Egypt. The Torah recounts how the Children of Israel were enslaved in Egypt by a Pharoah who feared them. After many generations of oppression, God speaks to an Israelite man named Moses and instructs him to go to Pharoah and let God’s people go free. Pharoah refuses, and Moses, acting as God’s messenger brings down a series of 10 plagues on Egypt.

The last plague was the Slaying of the Firstborn; God went through Egypt and killed each firstborn, but passed over the houses of the Israelites leaving their children unharmed. This plague was so terrible that Pharoah relented and let the Israelites leave.

Click below for a link to the Union for Reform Judaism website with more information.

What does the name of the holiday mean?

The name Pesach is derived from the Hebrew word pasach, which means “passed over.” It recalls the miraculous 10th plague when all the Egyptian firstborn were killed, but the Israelites were spared.

What is a seder?

A seder is an elaborate festive meal that takes place on the first night(s) of the holiday of Passover. The word seder literally means “order,” and the Passover Seder has 15 separate steps in its traditional order. These steps are laid out in the Haggaddah.

What is on a seder plate?

The contents of a seder plate vary by tradition, but most of them contain a shank bone, lettuce, an egg, greens, a bitter herb, and a mixture of apples, nuts and spices.

What is a haggadah?

The Haggadah (plural: haggadot) contains the text of the seder. There are many different haggadot: some concentrate on involving children in the seder; some concentrate on the sociological aspects of Passover; there are even historical haggadot and critical editions. You can choose the haggadah that matches the type of seder you want to have.

The Four Questions are traditionally asked by the youngest person at the seder who is capable of asking them. The version that appears in the Haggaddah is in Aramaic. In English they read:

Why is this night different from all other nights?

- On all other nights we eat both leavened and unleavened bread, but on this night we eat only unleavened bread.

- On all other nights we eat all kinds of vegetables, but on this night only bitter herbs.

- On all other nights we do not dip our food even once, but tonight we dip twice.

- On all other nights we eat either sitting up or reclining, but tonight we all recline.

The afikoman is half of the middle matzah that is broken in the 4th step of the seder, Yachatz.

It is traditional to hide the afikoman, and the person who finds it gets a prize! The afikoman is eaten last of all at the seder, during step 12 of the seder, Tzafun.

HIGH HOLY DAYS

Upcoming High Holy Day Services and Events

Click on the link below to view the latest updates regarding upcoming High Holy Day services and events.

WHAT'S HAPPENING

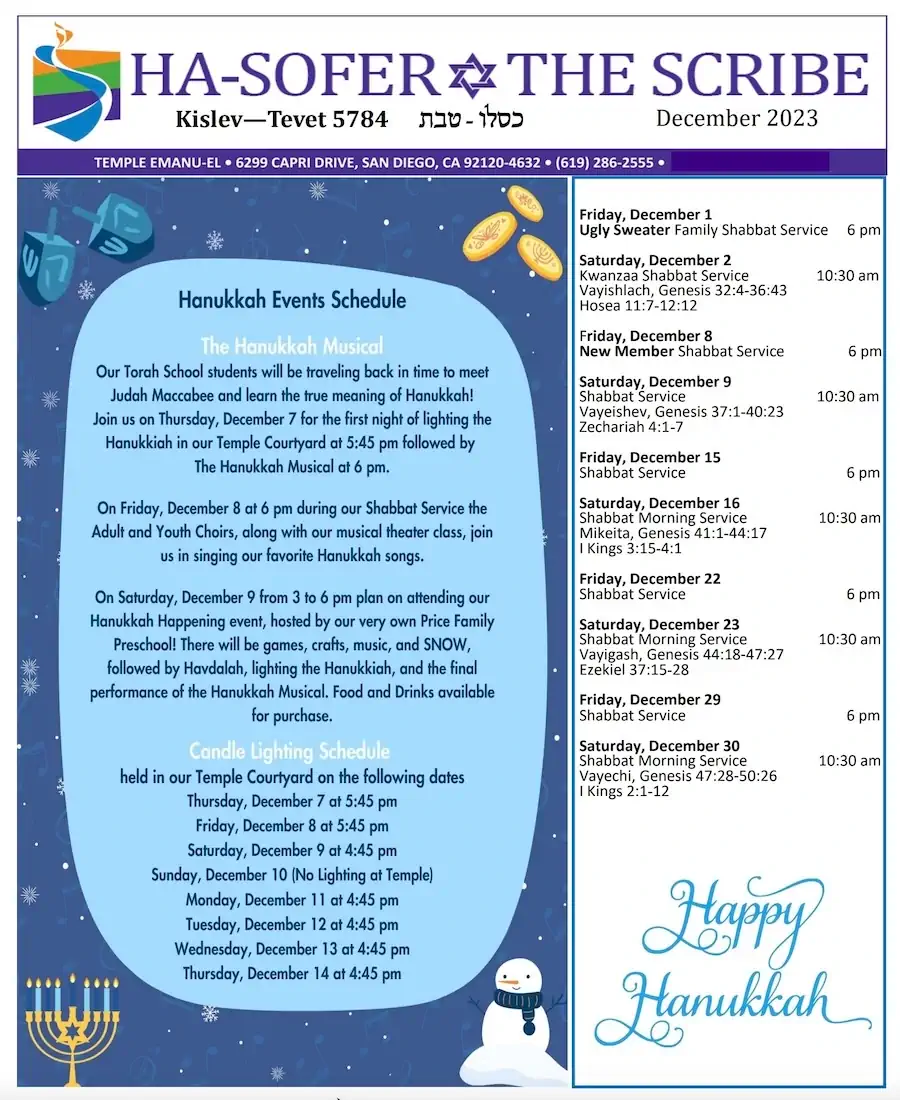

Bulletin

Read the official newsletter for Temple Emanu-El, Ha-Sofer (The Scribe).

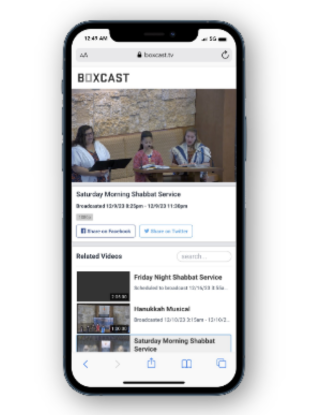

ON DEMAND STREAM

Services & Events

Stream live services or view past events on BoxCast TV.

6299 Capri Drive, San Diego, CA

(619) 286-2555

temple@teesd.org